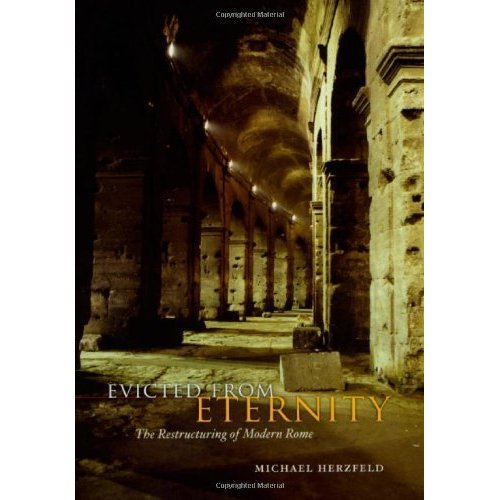

If you want to understand Romans and explore beyond their city’s glorious façade, devote your time to the suburb of Monti and Evicted from Eternity: The Restructuring of Modern Rome by Harvard University professor Michael Herzfeld. He writes wonderfully: this book reads like a novel but it is in fact a work of scholarship. Professor Herzfeld takes us deep into the narrow streets and charisma of Monti, which is home to the Colosseum. This is Rome’s most ancient district and for modern-day Romans it is also the centre of cool. Unfortunately, as Herzfeld shows, this means original Monticiani can no longer afford to live there. Monti is in some ways like a microcosm of Rome itself and offers a fascinating reflection of the irreversible processes of globalisation.

If you want to understand Romans and explore beyond their city’s glorious façade, devote your time to the suburb of Monti and Evicted from Eternity: The Restructuring of Modern Rome by Harvard University professor Michael Herzfeld. He writes wonderfully: this book reads like a novel but it is in fact a work of scholarship. Professor Herzfeld takes us deep into the narrow streets and charisma of Monti, which is home to the Colosseum. This is Rome’s most ancient district and for modern-day Romans it is also the centre of cool. Unfortunately, as Herzfeld shows, this means original Monticiani can no longer afford to live there. Monti is in some ways like a microcosm of Rome itself and offers a fascinating reflection of the irreversible processes of globalisation.

Romans are, in short, an ethnographer’s dream. And Monti offers an intense refraction of this seductive perversity, concentrating within a relatively narrow space artisans, merchants, and intellectuals and politicians

What do you think are some of the greatest misconceptions about running away to Italy and/or la dolce vita? For example, what are some of the main contradictions that Rome and Monti present to stranieri?

What do you think are some of the greatest misconceptions about running away to Italy and/or la dolce vita? For example, what are some of the main contradictions that Rome and Monti present to stranieri?

Visitors find Rome – and especially Monti – idyllic. In many ways Rome is idyllic: gorgeous architecture, stunning views, a vibrant musical life, fabulous and often relatively inexpensive restaurants, the cheerful daily rhythm of street life. But there is a powerful undercurrent of less attractive phenomena. People are being kicked out of their homes by a variety of implacable forces ranging from the underworld and the banks to religious institutions claiming a charitable identity. Loansharking is rife; so are prostitution, racism against immigrant populations, police intolerance, political extremism. The economic pressures that these facts indicate are being exacerbated by the current problems of the country as a whole and of the European Union, but in some form they have always been part of Roman life, and Romans know how to deal with them – not always successfully, but usually with aplomb and dignity. A foreigner who stays for a while, and especially one who speaks the language, will find a great deal of fascination in this play of light and shadow, this chiaroscuro, in the social realities of Rome today. And the presence of foreign visitors has also been a factor. You can’t have such a deep tradition of tourism, with its sometimes rather obsequious but almost always stylish self-presentation, and not expect to see hotels and bars disrupting what was once the quiet life of Monti’s side streets – repeating a process that had already happened in Trastevere and elsewhere. So those more sensitive foreigners who stay more than a few days will sense their involvement in the impact of a global economy that has sharpened the local inequalities and changed the social life of the city forever, while in some case deepening and sharpening other sources of discord and misery. All that said, Rome remains an extraordinarily resilient and infinitely delightful place, and the Romans – with their irreverent sense of humour and cheerful sociability (it’s not for nothing that they call themselves chiacchieroni, chatterboxes) – humanize what would otherwise be a dauntingly enormous treasure-house of aesthetic beauty.

Your book discusses the ambivalence that the other Italian cities and provinces feel for Rome. This is also common in other countries with their capital cities. Is there something extra to the way Italians, or Romans themselves, think of their national capital?

It’s certainly true that other capital cities are despised by country-folk. But Rome is a rather special case. For one thing, not many capital cities speak a dialect that is so distinct from the official national language. Yes, there’s London’s Cockney, but that’s more a matter of accent and the famous rhyming slang than a significantly different vocabulary or syntax. Much the same goes for the Paris argot. Berlin spoke a dialect, to be sure, but the German situation has been much more disrupted by post-World War II internal migration than the Italian. And Athens, which originally spoke a form of Albanian and a dialect of Greek that died out in the 19th century, is now taken as the standard-bearer of official Greek. Rome differs in other ways too – notably in its gastronomy. People only a few miles away don’t know about puntarelle, that salad of bitter young chicory that only lasts a few weeks in early spring in Rome; and the local Jewish food traditions are also quite distinctive. But most of all I find Romans themselves to be very proud of not being like other Italians and even to take a kind of perverse pride in being despised by their fellow-citizens. Some, even in high places, would even like to undermine Rome’s status as the national capital! I can’t think of any other capital city that I know where such attitudes are so strongly felt and expressed.

It’s true that the reasons for which other Italians look down on Rome (even while admitting that it is a beautiful place) do not always match or directly reciprocate the Romans’ own attitudes to the rest of the country. For example, Romans tend to view people from other cities as forestieri, outsiders, a term that can also mean “foreigners.” But other Italians sometimes look down on Romans as ministeriali, “ministry people” who might themselves not be of local origin, because Rome is, after all, the seat of the national government – which is why localist and separatist movements like the Northern League like to sneer at Rome as the source of what they claim are their fiscal and other sufferings.

In the beginning, when you began living in and studying Monti, what was your most difficult period or moment? And, at the other end of the journey, what has been the most rewarding?

It’s really hard to think of a difficult moment. I came to Monti with personal introductions, found friendly people in bars and restaurants, and came to rely on their proclivity for open and uninhibited conversation as a great resource. That’s why I described Romans as “an ethnographer’s dream.” In some places I’ve worked, I’ve had to confront deep suspicion of my motives. Here I was working with a relatively educated working- and middle-class population, a population that included, for example, two very learned taxi-drivers (they both collected old and historical books about the city and could discourse endlessly about the past) as well as artists of various kinds, scholars, and professionals with a considerable range of experience outside the city. Romans are supremely self-confident about the importance of their city and pretty steadfast in their nonchalance about others’ opinions of it.

There are always awkward moments when you think you’ve overstepped the bounds of propriety with invasive questions, or when you discover that some friendly neighbour is a bitter racist. But that is not unique to the anthropological experience; it’s human. And there were virtually no moments when I really felt I’d reached a dead end or encountered explicit hostility – except once, when someone stepped into a meeting I was filming (she must have been aware of what she was doing) and then objected to being filmed! I excised the passages in which she appeared and I gather from a mutual acquaintance that she was mollified, but it was, to be sure, a rather disconcerting moment – privacy is a lively issue in Italy, and my sense of anthropological ethics also made it imperative to try to satisfy her even though it was her own action that got her filmed in the first place.

But that small confrontation was a rare exception. The year my wife and I lived in Monti was one of our most joyful times and it was also professionally fascinating and, despite the painful topics I was investigating (especially the all-too-frequent evictions), richly rewarding. I’d like to think that my book reflects that sense of pleasure despite the very real anger I’ve expressed against the people who were ruining the lives of my friends there. (By the way, as a matter of record and since the question has been raised in a rather nasty way on the internet, I did not rent an apartment from which locals had been evicted; on the contrary, my landlord was one of the relatively few local owners still remaining – a charming man whose property had come to him by inheritance and on which he was making a small income that I assumed helped him meet the growing costs of maintenance and life in general. On another occasion, too, we rented from locals, and I hope that helped them resist the pressures to sell and get out. But of course the people who had the hardest situation was those whose homes belonged to institutions – banks, churches, confraternities, businesses – that had no interest in helping them remain where their families had lived for decades, even perhaps for centuries. That was hard; but my investigations of it never provoked any serious hostility that I came to hear about. And I think I would have heard about anything of that kind!

What is your advice for expats in Rome, those who have recently arrived, those who are enchanted and those who are at the end of their tether?

To the first group, I’d say, “Learn the language” – not necessarily the dialect, though you might well pick it up anyway once you’d got a good handle on the official form of Italian. Get out to the bars and restaurants – not the expensive ones, necessarily, but places where the food is delicious, the décor unpretentious, and the service friendly and unhurried. Monti has lots of those. Talk to people – they won’t take it amiss; it’s what they themselves do, after all. Don’t read your e-mail in a café. Let the people around you draw you into their social lives.

To the second group, I’d say that some people just don’t cope well with being in a foreign environment, although I think the ones who only hang out with their co-nationals are probably the least happy – they have a sense of being out of place, they develop negative stereotypes about the locals, and they can’t be bothered to learn the language and find all sorts of excuses for that. That happens in many countries; in Italy those people may well be a minority, but that must reinforce the sense of isolation that leads them to complain so much in the first place. So again – get out among the locals, learn the language, and avoid your co-nationals as much as you can without causing offence. Just keep in touch with one or two of them in case you need advice that locals really cannot give you. And learn from the locals themselves. The Romans have a big thing about having adapted to the harshness of life under papal rule for nearly two millennia; they are not fatalists, but they know how to roll with the punches. That’s a good model for living in a city where sometimes the bureaucracy can really get to you! Go to concerts (there are lots of them), walk around the city’s less well-known areas, discover places for yourselves. And when you get irritated about something, treat yourself to a really good meal with some excellent local wine and some of the best coffee in the world. It’s a very soothing formula!

In Evicted from Eternity, you wrote, “Those who purchase a share in the historic centre of a city such as Rome are claiming possession of a majestic civilizational status, one they contrast with the rough manners of the Roman working classes.” Could you expand on this here in relation to Monti’s original residents?

Monti is roughly coterminous with the ancient Subura – a red-light district then, as in fact part of Monti still is (though now only in a very minor way). Monti remained a largely working-class district until relatively recently – far longer than Trastevere, for example, although both were reviled for their supposedly ruffianly populations. The older families (I don’t like the word “original” because there’s always a lot of migration) represent that working-class identity, but there are fewer and fewer of them. Whereas in the old days – say, thirty or forty years ago – people who became rather more prosperous would aspire to a large suburban home, today owning a house in the centro storico, the historic core of the city, is a mark of status and prestige, an accoutrement that is expressed in terms of the antiquity and aesthetic richness of the city’s heritage. The locals take pride in these things, but they are more likely to mention the ghost of the Empress Messalina, the brothels of antiquity, and the scoundrels who form the heroes of much of the local lore. Those who move into the bijou apartments now being carved out of the old palazzi look down on such attitudes and the people who hold them. They want to link their claims on a direct link with antiquity to civilizational models that have little or no tolerance for the salty humour of the Roman working classes – although we know that ancient Rome had its very seamy side, perhaps an even seamier side than most of what we can find in the city today.

Now that you no longer live in Italy, what are the four things you miss the most?

It’s not actually quite accurate to represent me as not living there – I go back often, and sometimes for long periods. So let me list the things I most look forward to when I do that. First and foremost, there are my Roman friends – people who have contributed so much to my understanding not only of their wonderful city by also of humanity in general. Then I’d say that the pace of everyday life in Rome appeals enormously to me; I rather enjoy the hustle and bustle, which to me signal great energy, but I also love the calm moments in a favourite restaurant or sitting in the main square of Monti. Third, I look forward to the intense conversations and the deep political engagement that makes Italy in general, and Rome in particular, both perplexing and fascinating. And fourth, and this is also a very important part of my answer, I love just being able to saunter out from wherever I’m living and realizing that this city still makes a living, breathing presence out of its complex past – and that it does so in ways that constantly catch my attention, surprise me, and on occasion bring tears of sheer pleasure to my eyes as they feast on the extraordinary beauty that even the greatest corruption can generate.

Really like it. Well done.

Excellent interview! Some very interesting insights into the complexity and beauty of Rome.

Thanks! Glad you like it Catherine 🙂

Wonderful interview and insights into Rome.

Hana, congratulations, a great interview! Whenever I stop in Rome on the way to my native Puglia it never fails to surprise me with some new discoveries – whether that be some wonderful monument or the inside of a church. As for the Romans… love them. Well done!!!