Best portraits of Rome

‘In other places one searches for sights of interest; here they crowd in on one. Every kind of vista confronts you – so close they could be sketched on a single sheet,’ to quote Goethe’s ‘Italian Journey. ‘One would need a thousand styluses to write with. What can one do with a single pen?’ While, indeed, no library would suffice for literary depictions, paintings of the ‘Città eterna’, at least until the 17th century, are rare.

True, the city is featured in any number of bas-reliefs and in the works of various Renaissance artists, but always in the background. A tiny and distant version of Marcus Aurelius’s horse pops up in Filippino Lippi’s “Santa Maria Sopra Minerva” frescoes. A typical and miraculously-lit Roman ‘overdoor’ appears in Raphael’s fresco of St. Peter in Prison. In the other Raphael rooms, you can see the city in flames (under an early Pope Leo) and, courtesy of Giulio Romano, a Tiber scene teeming with drowning soldiers. Yet event, not cityscape, is the focus.

As a visit to Museo di Roma proves, only in the 1600s does Rome begin to be depicted. A colony of North European so-called ‘vedutisti’ (landscape painters) had already established themselves here, working and also carousing. Pub-crawls were nothing new, and Roland van Laer’s depiction of a boozy northern artist’s initiation ceremony provides a window into the ‘vedutisti’ lifestyle. In Laer’s scene, blades smoke pipes, guitarists mount ladders and a red-stockinged hostess on top of a human pyramid balances two flagons of wine on her head. Behind, a ‘writer’ daubs graffiti to Venus and Bacchus as one devotee of the latter is seen sprawled upon the floor.

More sober are the Dutch views of pre-Valadier Piazza del Popolo, then more of a meadow than square, of San Giovanni with its recently constructed obelisk, and of the Ripa, Rome’s once thriving port. In another work, via del Corso lives up to its name and you can see Barbary horse-racing along the famous street. One Adrian Magiard, depicts a football match at the Quirinale terrace which doubles as the straight-lined ‘curva sud’ (south stand) of today’s stadio Olimpico.

Italian painters were quick to catch on. Eventual ‘maestro’ to Claude Lorrain, Agostino Tassi, produced cityscapes, along with landscapes and seascapes. His ‘May Day on the Campidoglio’ (1631) revolves around the specially-planted slippery tree of abundance, a fascinating documentation of an event gone by. Daredevils perch like birds for a free and perilous meal, while behind the Palazzo dei Conservatori, clouds queue up as in some Old Flemish masterpiece. The cinematically sized ‘Fair day in piazza Navona’, (an event that has since vanished) is a depiction of a sort of urban Ascot opening day. So much is going on, that the painting is divided between three, a common custom –namely Sacchi, Gagliardi and Manciolo.

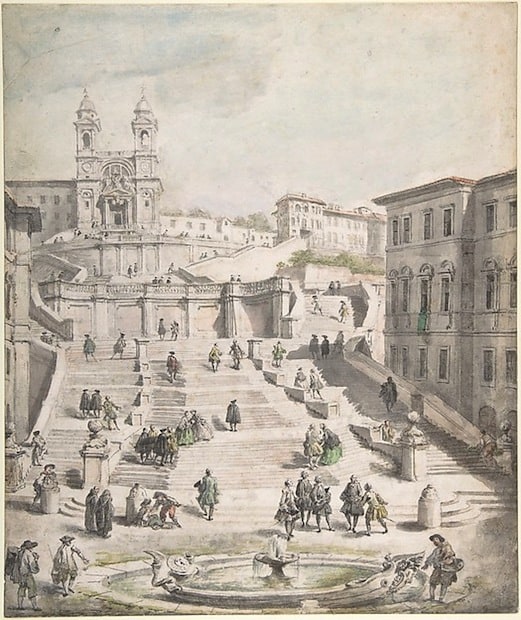

With the Grand Tour, painting the city became big business: ‘Views’ with or without the clients present (the day’s pre-photographic ‘selfie’) was a Grand Tourist’s ‘must have’. Although he is better known for painting Venice, Canaletto, a supplier of panoramas to the English upper crust, cut his artistic teeth in Rome. With Joseph Smith, English ambassador, acting as his agent/wheeler-dealer, some views (of the Coliseum, for example) are in the Royal Collection, others in country houses, and others were sold and brought to America. To meet demand, Canaletto’s mentor, Giovanni Panini had no qualms about cramming as many landmarks as possible into one picture. In one view the Dying Gaul finds itself resituated below Trajan’s column, which was relocated within a blink of the Coliseum. In his ‘Gallery of pictures of ancient Rome’ (now in New York’s Met) canvases – whether Panini’s or anyone else’s – are shown stacked factory-fashion, making him the Andy Warhol of the antique.

Soon, a whole wave of European artists had joined the craze. Indeed Museo di Roma’s annex features, under the title ‘Luoghi comuni’, a rotating collection of landcape/cityscapes – according to the nationality of the artists – German, British, French. Right now it’s the Germans’ turn: Pride of place goes to Jakob Hackert, painter to Catherine of Russia, and friend and art teacher of Goethe himself. One side of his ‘Aniene Waterfall at Tivoli’ is torrential white, while the other shows beetling cliff and verdure capped by acrobatic houses from which a maid quietly hangs out washing. One vedutista depicts Titus’ Arch before Valadier’s restoration; another commemorates a fraternity of German artists gathered to interrogate the Sybil before they all retire for lunch.

Some depictions of Rome are more tangential, such as the quintessentially English portrait of Catherine Bishopp. Featured in the museum’s permanent collection, the portrait of girl posing and holding a dove replicates an ancient statue which painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792, also famous for founding England’s ‘Royal Academy) had sketched in his notebook during his stay in Rome some years before.

For 20th century pictures of Rome – by mostly Roman artists, it is best to visit Villa Torlonia’s Museo di Scuola Romana. ‘With close local links and a deep distaste for art as an expression of a political regime,’ the Scuola Romana movement positioned itself against Fascism.

Historical justice or irony, many of its works are now housed on the 3rd floor of the same building which Mussolini made his home in the 1930s for a nominal rent of 1 lira year. The first floor, complete with a bunker, has photos of the dictator horse-riding, gardening, playing tennis, and the second floor dining room is frescoed with the triumphs of Alexander. Just a stairway away Renzo Vespasiani’s starkly graphic pen and water-colour fixes a ‘Victim at Tiburtina Station’. Hinting at the deportations of 1944 is Vespasiani’s sinisterly dark ‘Trains at Portonaccio.’

‘Anxiety, reaction against rhetoric, a city in its most hidden places and about to disappear under the pickaxe of Mussolini’s demolition projects,’ describes the catalogue. The description also fits Mario Mafai’s series called ‘Demolizioni’, showing ripped inner walls gaping like wounds (on occasional display in via Crispi’s Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna.) Carlo Levi, also affiliated with la Scuola Romana, ended up in internal exile, writing the famous memoir Christ stopped in Eboli. In his painting here, as a sign of the times, an aqueduct – that eighth wonder of the world and archetype of the public good – turns an alarming and symbolic red.

Back to the GNAM museum. one of the Futurist rooms gives an idea of what the Scuola Romana were reacting against. Dottori’s bombastic ‘Polittico Della Revoluzione Fascista’ flaunts ranked machines, human or otherwise. The adjacent ‘militiaman’ sculpture is all brawn and metal below an under-sized brutish head, while opposite, as an antidote (and in a totally different style) is a gorily chastening 1944 picture of Piazza Loreto.

A few rooms down, Giacomo Balla’s 1910 multiple pointillistic ‘Villa Borghese’ comes as a breath of fresh air. A window with a difference, its ‘divisionistic’ technique recalls, at the other end of the century, David Hockney’s ‘A bigger splash.’ Going back further, Giovanni Fauré’s 1835 Colosseum shows a space devoid of tourists with inner terraces tufted with greenery as again recognition and surprise combine to reach places postcards cannot.

Fast-forwarding to the museum’s 1950s and 60s collection, views of Rome become more abstract. That said, Emilio Vedova’s ‘Scontro di situazioni’ could offer a ‘mindscape’ of Porta Maggiore at rush hour; Soto’s ‘Gran Muro Panorimica Vibrante’ with a gulp of imagination might be glimpsed from any local rooftop, especially in the days of Rome’s famous ‘ottobrate.’