The first spike was in 2011, when 63,000 migrants arrived in Italy by sea. The second spike, in 2013, was almost three times the first, 170,000. And it held. For the last four years, 150,000 to 180,000 migrants have arrived in Italy, and 2017 is predicted to supersede these numbers.

As Rome staggers under the pressure, news stories abound about the migrant who is sleeping in a government-sponsored shelter without water or electricity, waiting months or years for legal papers, and corrupt individuals who profit from the 36 euro daily rate for housing and food providers. As Italy negotiates with the EU about which countries will take how many, this past Easter weekend over 8,000 migrants were rescued and brought to Italy by the Italian Coast Guard. In the midst of this humanitarian crisis, some refugees find their way, helped along by those who step forward to make a difference.

“I came here with ten friends. I am the only one remaining in Italy,” Mansur Nadri tells me on a stone bench in the courtyard of St. Paul’s Within the Walls Episcopal church, where he works as a peacekeeper at the Joel Nafuma Refugee Center (JNRC). In 2010, Nadri migrated from Afghanistan. In the interim, his original companions have found their way north, to Germany, the UK, and other countries. Nadri has seen most of his cohorts move on, but has chosen to put down roots in Rome. He speaks Italian, and is on track for citizenship in the next five years.

On another stone bench at JNRC, 37 year old Dosso Djene from Ivory Coast spoke about her dilemma: should she wait three years until she could start a nursing course, or take a waiter’s course sooner? She arrived in Italy in 2010 and, seven patient years later, has managed to find two reasonable options for future employment.

I met Djene and Nadri because I teach English at the JNRC, the only day center in the city, which provides food, clothing, language classes, therapy, legal support, and as of April, computer classes. The only free English classes on offer in Rome, some students commute hours to take part. My class is mostly young men from West Africa and the Middle East, eager and motivated, full of hope for a better life. One day, when we were reviewing the future tense, I asked a question about cities, and movement. It wasn’t directed at their current lives, but it was interpreted that way. Getting out of Rome was the unanimous answer to a question I didn’t ask, a testament to the opportunities and social services available.

“What refugees need most is a job, a house, and documents. To learn the language, and culture, of their new home. This is how they maintain their dignity,” says Ejaz Amhad, a journalist and cultural mediator who migrated from Pakistan almost three decades ago. His work with government agencies, hospitals and schools puts him in contact with hundreds of migrants, who wait months or years to get their papers or a job. “People panic. They get depressed,” he observes.

Outside of Rome, some government officials have stepped forward to create more hospitable conditions. Leoluca Orlando, the mayor of Palermo, has made his city a port of welcome, questioning the distinction between economic and political migrants. After two months of residency in Palermo, any migrant gains the right to work legally, in addition to school and medical care.

A smaller village in Southern Italy, Sant’Alessio, has made the most of the influx of young, eager workers to revitalize their economy. The village provides housing, social services, and jobs to refugees, and has been able to keep schools and other businesses open as a result. Their win-win approach is now being adopted by four other villages in the area.

Closer to Rome, there are other pockets of hope.

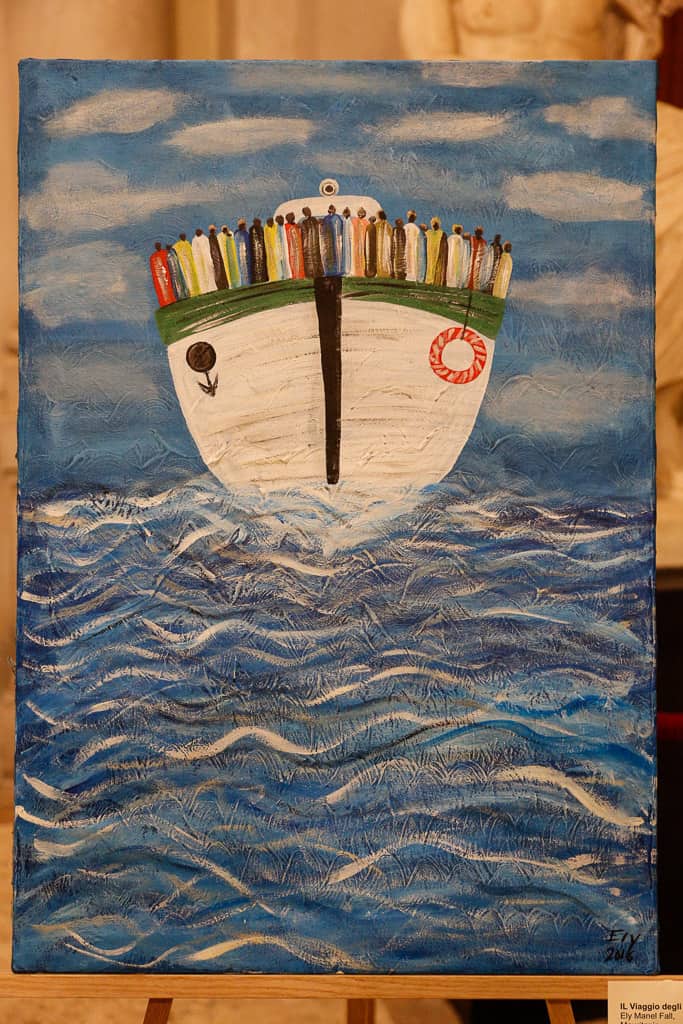

The Joel Nafuma Refugee Center, referenced above, has just opened a computer lab with donations from the US Embassy and will offer training and classes in addition to running a day center, providing breakfast, clothing, tailor training, interview skills, classes in English and Italian, literacy, counseling, art and music therapy, and more.

jnrc.it

Doctors for Human Rights Italy (MEDU) has been providing treatment, screening, and education through mobile clinics since 2004. Their work with the homeless extends to a growing refugee population.

Altrove, a trendy restaurant between Ostiense and Garbatella, trains young people ages 16 – 25 to be chefs, bartenders, and wait staff, and employs a portion of their graduates. The project grew out of educational work at the Centro Informazione e Educazione allo Sviluppo to offer practical skills and a job for the disadvantaged. Altrove selects students for their school based on need, and liaises with local associations who work with refugees as well as residents.

altroveristorante.it

With a focus on minors and women, the Centro Astalli offers housing, social services, a school, and outpatient care in four locations in Rome. Run under the umbrella of the Jesuit Refugee Service, they serve 400 meals a day across the city.

centroastalli.it

The first stop for many migrants is the Centro Baobab near Tiburtina Station, which offers housing, meals, psychological support, healthcare, legal assistance, clothes, and more.

baobabexperience.org

As part of the city’s community, there is much we can do to help, in the short and long-term. All of the institutions above depend on donations in cash, goods, and volunteers. For more information, visit their websites.