Rome’s historic centre is a labyrinth of cobbled backstreets emerging onto open piazzas. But what you see on today’s street level tells just half the city’s story. Buried beneath Rome’s piazzas is a hidden world of mammoth ancient structures that rival the ground-level wonders of the Pantheon and the Colosseum and preserve some of the city’s most shocking secrets and stories. Here are some of our favourite.

Piazza San Cosimato & Rome’s Naval Colosseum

Locals know Trastevere’s Piazza San Cosimato for its bustling daytime market and evening open-air cinema. What few people know is that this square was once the site of naval gladiatorial battles (naumachia) inaugurated by the emperor Augustus in the first century BC.

From the beginning of the Imperial Age, the area beneath San Cosimato was an aquatic Colosseum where marine gladiators would battle to the death—smacking each other with oars and stabbing each other with swords in recreation of naval battles like Salamis and Actium.

The Naumachia was large enough to accommodate 30 ships and more than 3,000 participants. No literature survives documenting in detail the spectacles that took place, but they must have rivalled those of the Colosseum, which would not be built for another 80-or-so years.

The Naumachia’s basin alone measured a staggering 533 by 355 metres, and was fed by an aqueduct running down the Janiculum Hill. We know about the naumachia and its dimensions because Augustus boasted about it in his Res Gestae (literally ‘Things I’ve Gone and Done’) – an autobiographical list of achievements Augustus disseminated throughout the Roman Empire but visible in Rome on the side of the Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace).

Piazza Navona & the Stadium Beneath

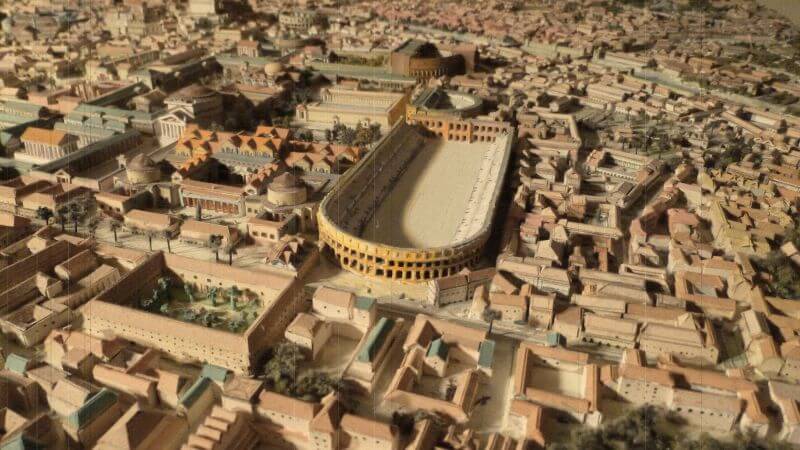

What first strikes you about Rome’s most famous square is that it’s not actually a square, but a kind of long, elliptic shape. That’s because Piazza Navona stands atop the filled-in foundations of a first-century CE stadium built by the mad, bad, and dangerous-to-know emperor Domitian.

If we are to believe Suetonius, our source of ancient gossip for the times, the emperor Domitian was particularly passionate about four things: stabbing flies with his stylus, writing hair-care manuals to tackle his premature balding, tormenting the Roman Senate, and promoting Greek-style physical contests.

His stadium wasn’t a chariot-racing track (though you’d be forgiven for thinking it was, given the shape) but instead played host to foot-racing and wrestling contests. You can visit part of the stadium today, although not a great deal remains. If you want a better idea of how an ancient stadium looked, check out the Villa of Maxentius just off the Via Appia.

Today, Piazza Navona is best known for its fountains, especially Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers in the centre and Domitian’s Obelisk protruding out of it. We can no longer cool off in its fountains during the scorching summer months; attempting to do so will land you with a hefty fine. But this wasn’t always the case.

Every August weekend between the completion of Bernini’s fountains in 1651 and the raising of the piazza’s level in 1867, the Romans would plug the fountains and flood the piazza. The city’s rich would then ride around in horse-drawn carriages splashing the spectators on the sides—ostensibly to cool them off, more likely just because they could—and the city’s populace would splash and bathe in the square to get some temporary respite from the heat.

Piazza de’ Massimi and Domitian’s Odeon

Right at the top of Piazza Navona is a much smaller piazza that few people ever notice and even fewer take the trouble to explore. Its name is Piazza de’ Massimi (the Square of the Massimi), and it takes its name from the Massimi family, who have formed part of the Roman aristocracy since 999.

The façace of the Massimi’s palace is worth seeing in itself, depicting scenes from the Old and New testaments. But it’s the freestanding marble column in the centre that draws the most attention, and its origins will surprise you.

The column comes from the emperor Domitian’s Odeon. Built at the same time as the stadium that underlies Piazza Navona, the Odeon served as a theatre that could accommodate 11,000 spectators to enjoy plays and musical performances. Position yourself in the centre of the square and you’re standing on where the stage would have been.

Two signs in the shape of its buildings give away the structure that lies beneath. Firstly there’s the curve in the Palazzo del Convento di San Pantaleo; secondly there’s the more noticeable curve in the building on the main road of Corso Vittorio Emanuele.

We don’t know much about what exactly took place on stage. But other references to Roman theatre suggest it might not have always been pretty.

Since the bloody spectacles of the Colosseum had become the hottest ticket in town in the 80s AD, theatres had to vie for the attention of the Roman populace by injecting more violence into their spectacles. We have evidence of real sword fights taking place on stage, and prisoners being switched with actors for the final act and castrated or even burned to death on stage.

Saint Peter’s Square and Caligula’s Circus

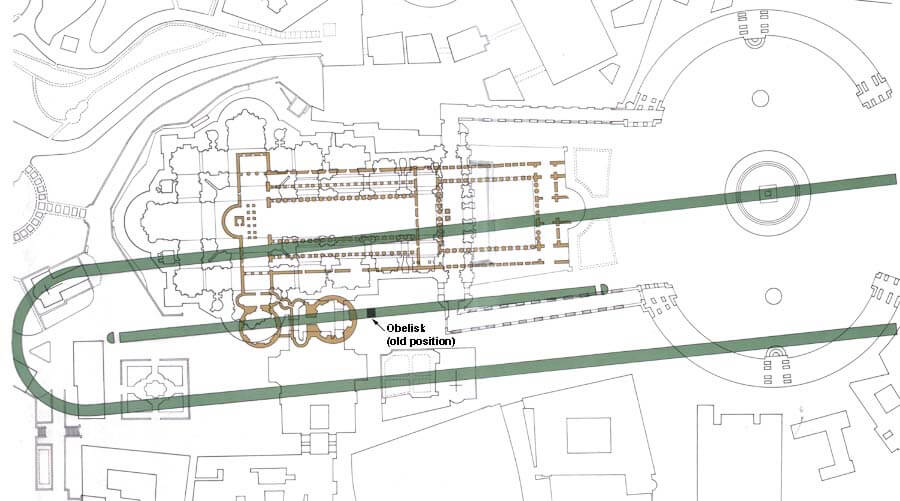

Standing in the centre of Piazza San Pietro, soaking in the sights of Bernini’s surrounding colonnade and gazing up at Saint Peter’s Basilica and Michelangelo’s dome, you would never imagine that anything as impressive could also lie beneath. But Saint Peter’s Square sits atop yet another ancient structure that would have wowed its ancient crowds: the Circus of Caligula.

Constructed in the first century CE, the circus occupied part of the sprawling imperial gardens inherited by the emperor Caligula. It certainly would have hosted chariot races, for which Caligula was particularly passionate. But the circus is most famous as the place where Saint Peter and Paul were executed.

Okay, so we’re not 100% sure that this was really the place. Instead, this theory comes from merging together two ancient sources—one which states that Nero used his circus for Christian executions following the Great Fire of 64 CE; another stating that Peter and Paul were martyred in Rome.

Nothing remains of the circus today, except the enormous obelisk that stands in the centre of the square. The Vatican’s obelisk was brought to Rome during the reign of Caligula (37 – 41 CE) and erected in his gardens and circus before occupying the central spina (barrier) of Nero’s Circus. You might be surprised to learn that this is the only obelisk in Rome that has never fallen, remaining pretty much in situ for nearly 2,000 years.

Campo de’ Fiori

Literally translating as Field of Flowers, today Campo de’ Fiori is nothing of the sort. We know that this area outside the Severan Walls was occupied by fields until the 14th century, but the floral origins of its name are shrouded in uncertainty. One farfetched theory goes that this area was named after a lover of Pompey the Great called Flora, but in likelihood the name was purely descriptive.

Campo de’ Fiori is famous for a few reasons. It’s a hub of Roman nightlife; the only piazza in Rome without a church; and home to Rome’s most bustling farmers’ market. Today, the Field of Flowers is one of Rome’s prettiest piazzas, but from the Middle Ages it wasn’t a place for the faint of heart.

Campo de’ Fiori was the site of many of medieval Rome’s public executions, as symbolised by the statue that stands in the square’s centre. On February 16th, 1600, the philosopher and Dominican friar Giardano Bruno was burned at the stake here on charges of heresy. It was only towards the end of the 19th century that a group of republican university students rehabilitated his reputation, commissioning a bronze statue of him to be erected in the centre of the square which defiantly faces the Vatican.

Join a walking tour of Rome and delve deeper into Roman history

Visiting Rome soon? Getting your bearings around the historic centre and visiting all its main attractions can seem a daunting task, especially for first-time visitors. Join one of Carpe Diem Rome’s walking tours and uncover the hidden history of the Italian capital.